“It takes courage for families to come to schools”: Midvale staff strive to build trust with Spanish-speaking, Latino families

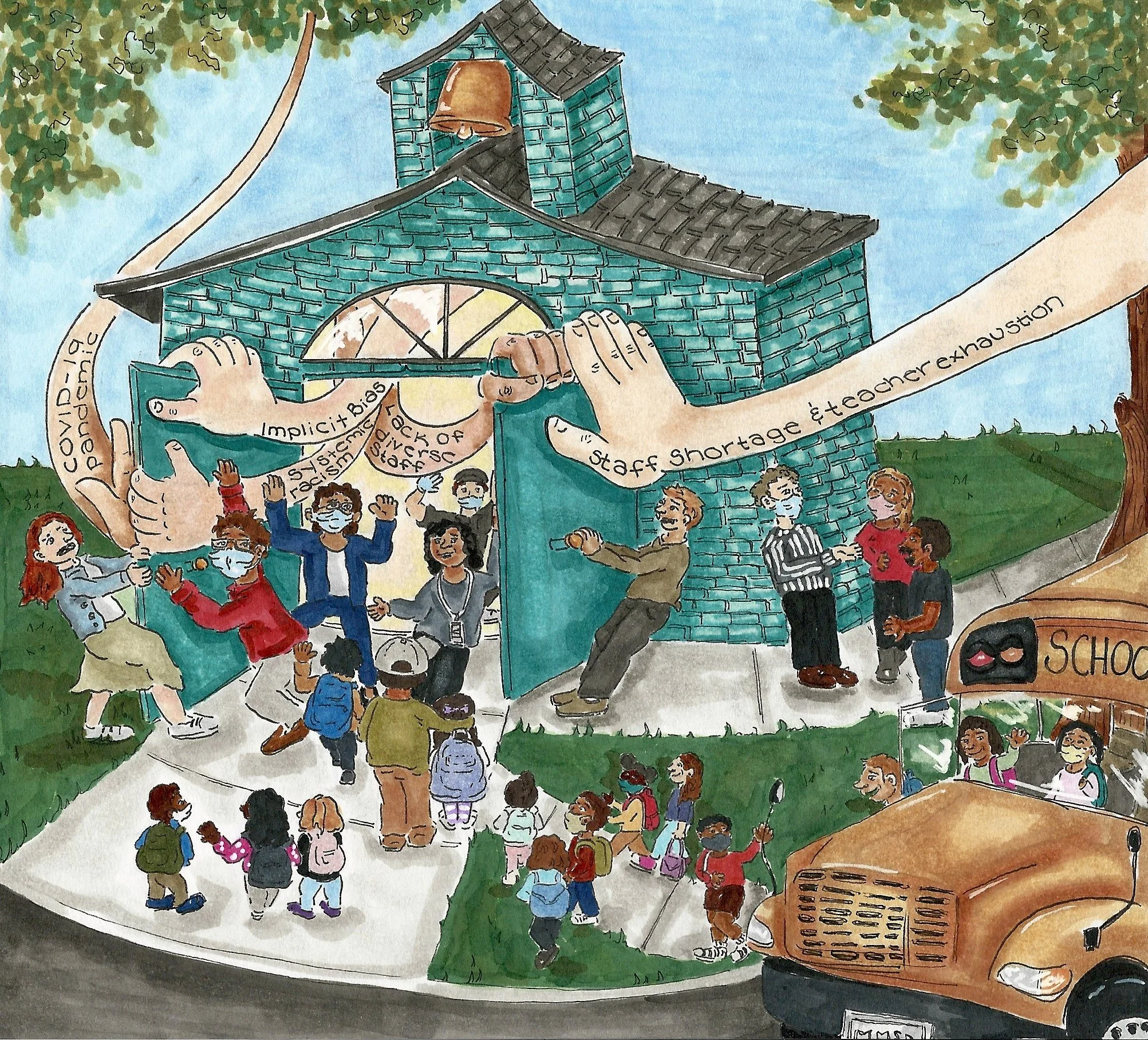

With the loss of Title I funding for the 2022-23 school year, dual-language immersion teachers and social workers remain concerned about the underreporting of needs as they seek to supplement the loss.

Midvale Elementary lost its Title I funding for the 2022-23 school year as free and reduced lunch application dwindled. However, according to second grade dual-language immersion (DLI) teacher Joe Schwebke, this loss does not accurately reflect the needs of the school’s families.

Midvale is one of the 20 schools in the Madison Metropolitain School District (MMSD) offering a DLI program, fostering 50% native Spanish-speaking students in an environment that values Spanish culture. Half the school day is conducted in Spanish and half in English.

A visit from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in 2018 shocked Midvale’s community, as, according to Schwebke, a number of the undocumented immigrants detained in Dane County were from the very neighborhoods that were home to many of the school’s Spanish-speaking and Latino families. This visit exacerbated fear in these neighborhoods and contributed to current underreporting of needs through federal documents required for Title I qualification.

“[Teachers] heard things from parents … they could look out their window and see this happening,” said Schwebke. “And the fear that went with that for families hasn’t gone away.”

Schwebke was one of many teachers and staff members who recognized an opportunity for schools to reach out to Spanish-speaking and Latino families and support them as a non-federal organization.

First grade DLI teacher Nick Welton understood connecting with and helping families required a rebuilding of trust.

“It takes courage for families to come to schools, because they could be new to the country, they could have had their own awful experience with schools,” Welton said.

Schwebke said earning the trust of families grows evermore important as Midvale approaches next school year.

“We’re definitely going to feel it next year without Title I funding,” said Schwebke. “That’s pretty essential for some of those tier three services that we need to provide to students in terms of their education.”

Lack of engagement on a district level

Schwebke said he already felt disheartened by consequences of the nation-wide teacher shortage to which the Madison Metropolitan School District was no exception.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated impacts of the teacher shortage in MMSD, bringing district officials like Executive Director of Curriculum and Instruction, Kaylee Jackson, back into the classroom.

However, Schwebke couldn’t help but notice the department that handles all DLI, which used to be known as the Office of Multilingual Global Education, took one of the hardest hits. Around 2016, this department worked toward expanding DLI presence in schools including a three year plan to increase staff certified in English as a Second Language (ESL) instruction.

“Several people who used to work there were transferred to other duties,” Schwebke said. “As far as [DLI teachers] know, there’s really only one person now, generally handling DLI support for those schools that have it … so that withdrawal of support for us has meant we have a curriculum that we … never received really robust training on.

“... to see that department sort of drained of its resources, and other things not, it seems to be this message, well, DLI is not a priority right now,” continued Schwebke. “That, to me, is the same as saying Spanish speaking families are not a priority right now because the vast majority of our Spanish speaking families do enroll in these DLI programs.”

At the beginning of the year, MMSD announced a budget plan to work toward becoming an “anti-racist organization,” through race and equity cirriculum, which, according to Jackson, requires family engagement.

“Because race and equity plays out in so many different ways, it’s not just a lesson, right?” pondered Jackson. “It’s a mindset. It’s a way that we engage with students every day … a way of interacting with students and with family members that [is] … responsive to their place.”

Midvale social worker Shaya Schreiber said she approaches her job with students’ families and home life in mind as well. This fueled her collaboration with social workers from other West High feeder schools to help families apply for resources through the Madison West High Area Collaborative.

According to their website, as a non-legal entity, but rather a group of community members and “school district staff working collectively in partnership with community organizations,” the Collaborative helps families meet needs anywhere from cleaning supplies to financial aid.

Though Schreiber said school principals tended to support this endeavor whole-heartedly and allowed social workers to make food and supply deliveries during the school day, not everyone recognized the value of building trusting relationships with families to help them meet every day needs.

“So I mean, to me, I feel like [learning and home life] is connected,” said Schreiber. “But I know that some people in education don’t see it quite so connected and I think that was a bit of a hurdle for us.”

Teacher Solutions

The Madison West High Area Collaborative:

Despite this “hurdle,” as of Fall 2021, the Collaborative had supported 62 households in the Madison West area home to 162 children total averaging $703 of aid per request since it started in April of 2020. Since September, $58,148.67 has been awarded out of the total $215,000 contributed to helping families meet basic needs.

These achievements would not have been possible without the group of social workers who, according to Schreiber, decided to work together in conjunction with the Midvale-Lincoln Parent-Teacher Organization (PTO) and and Joining Forces for Families (JFF) “to meet the needs of [families] and ensure [they] follow any legal guidelines within the school district.”

Schreiber said social workers assumed responsibility, communicating families’ needs with the PTO and JFF. Both of these organizations decided which requests would get approved and met from a pot of money held within the Midvale-Lincoln PTO pooled from all of the West feeder schools.

“Currently, I’ve been the social worker who’s been communicating with the Collaborative as far as needs for rent, utilities, any other type of financial assistance,” Schreiber said.

As of Fall 2021, the leading requests met by the Collaborative were for past rent due at 34.7% followed by assistance paying bills such as electric and internet bills at 31.9%.

Efforts by Schreiber and her team did not just alleviate financial stress on families, but also worked toward rebuilding trust between MMSD schools, and Spanish-speaking and Latino families.

Schreiber made sure to maximize accessibility of the Collaborative by making sure teachers knew about othis opportunity, especially teachers in the DLI program.

“I make sure that the [DLI] teachers know this is a resource,” said Schreiber, So when they hear from families, and they hear of a concern, you know, mostly communicating in Spanish with them that they can say, I think I know something we can do to help you, and they direct them to me or find out what the needs are.”

Welton said unlike government programs with application windows, the Collaborative provided many of his students’ families with a program unlike anything they’ve had access to before.

“There’s no other programs like it in the fact that it doesn’t close … there’s a limited fund of money, but it’s not a fund that closes,” said Welton.

Schreiber said parents were “really relieved” knowing social workers like Schreiber “were able to help in a way they thought they couldn’t find a way to help” by providing them with a direct line of communication.

“[This program] really cuts down on a lot of the bureaucracy and red tape,” said Schreiber. “It’s direct communication and getting answers quickly and we can figure out what needs to go on.”

Welton and Schreiber both acknowledged Midvale Bilingual Resource Specialist (BRS) Neliette Tijerino’s crucial role, working closely with Schreiber as a translator and resource for Spanish-speaking families.

“[Schreiber] has been on the phone for many, many hours with Tijerino talking to families to help them get forms filled out, and helping then find programs to the city that they could have access to and apply to for rent assistance,” said Welton.

Schreiber reiterated this, underscoring that Tijerino works reguarly with local community organizations that support Midvale families.

Collective efforts helped fill 24 requests total from Midvale (grades K-2) and its sister-school Lincoln Elementary (grades 3-5) at 12 requests each. Combined, Midvale-Lincoln was the top supported school system followed by Thoreau Elementary with 22 requests met. Additionally, 14% of those helped reported they identified as LatinX and 7% identified as multiracial.

Dual-Language Immersion Teachers:

DLI teachers developed and planned ways to ease engagement for Spanish-speaking and Latino families, Welton said. They implemented things as simple as offering first dibs for parent-teacher conferences to Spanish-speaking families who may not always have access to email to “be a little more equity driven and centered.”

“Generally [Spanish-speaking and Latino] families are working families,” said Welton, “So they don’t always have the availability to take leftover slots, necessarily.”

Schwebke also considered family circumstances, especially throughout the pandemic. “Especially with our Spanish-speaking families, they also tend to have older generations living within the same household,” Schwebke said. “They’re going to be naturally more cautious with how much they’re going to be going out and mixing in with a wider population possibly for fear of bringing home this infection that could cause some really serious problems for their household.”

Though Schwebke reported district-wide initiatives during COVID-19 did not extend beyond virtual technology training, many school principals including Midvale’s supported groups of teachers hoping to maintain engagement and trust with families.

Schwebke said Midvale needs tracked by social workers like Schreiber were not just sent to the Collaborative, but in the beginning of the pandemic, he and other classroom teachers went out to make deliveries to families on their own time.“There were definitely a lot of needs, especially from our Spanish-speaking families … if they weren’t going out, or if they had jobs, if their jobs were impacted, if they lost their job, all of those things made it more difficult for them to get what they needed.”

“We were able to help families get what they needed, certainly in terms of academic supplies, and then of course other needs as well,” Schwebke continued. “We came together for that because we knew they needed it.”

Schwebke said these deliveries also fostered interpersonal connections and trust.

“We also have families that have multiple siblings that have come through [Midvale] so a lot of us knew some families pretty well. So that was actually kind of nice to connect in that way even if it was to talk from a far, just to get that connection because otherwise, we didn’t see them in person at all.”

What needs to be done:

According to Schwebke, the DLI program brings Spanish-speaking and non-Spanish speaking families together in the face of geographical divisions.

“A lot of the [families who do not speak Spanish as a primary language] will ask us how can we help our student practice Spanish?” said Schwebke. “One [of] the things we’ll say is ‘hey, have a playdate with a Spanish-speaking friend and … half the time you speak Spanish and half the time you speak English.’”

Schwebke realized a lot of the connections are facilitated by teachers “unless the families themselves already have some investments in the Spanish-speaking community.”

“I could even say this about my class this year, half of them are getting picked up at the end of the day and they’re going to aftercare to get picked up later right at dismissal time, and the other half are all taking a bus to get home,” said Schwebke. “Like you see that get highlighted and that’s another whole conversation about how you sort of break that barrier down but it’s definitely something noticeable.

Steps taken to bridge families by DLI instructors are something Schwebke believes should be amplified by the district beyond the DLI program and beyond Midvale to encourage trust not just within the school, but in the entire MMSD community where 22.3% of students identify as Hispanic or Latino.

“I think the [ability to focus on Spanish-speaking families] is something that’s been deprioritized by the district either through indirect actions or direct actions and I don’t want to see our DLI programs lose out, I don’t want to see them disappear,” Schwebke said. “I want it to be a thing where people want to come to Madison because of [it]. I think [DLI] should be something we champion in some way.”

Schwebke explained although Midvale is lucky to have a steady Spanish-speaking population, the district would close DLI opportunities if enrollment of Spanish-speaking families dropped below a certain number.

“For it to be something that’s based entirely on predicted numbers, that also sort of says we don’t value it,” Schwebke said.

Non-Spanish-speaking families enter a lottery in the hopes of enrolling their child in DLI due to the program’s popularity.

“Parents generally have a lot of power to move things in our district but again the most active populations … tend to be affluent families who are mostly white and not native Spanish-speaking,” Schwebke said. “And so that voice, even in DLI … it should seem like Spanish-speaking families should have an equal voice is … the truth is they don’t because of the dynamics of how the program is populated in the first place.”

However, despite necessary structural changes, DLI is a program that Schwebke said uniquely “values culture, specifically Latino culture” because most of Midvale’s Spanish-speaking students are from Central America.

“If a district were to emphasize that, to prioritize that, that’s sending a huge message to families … we do care about you and here’s how we do it: we’re specifically teaching both languages, we wants our students to be biliterate and bicultural,” Schwebke remarked.

As for now, centering families’ voices within the schools remains essential.

“If you’re gonna get families on your side, then you have to take everything about them into consideration,” Schwebke said.